he previously unknown ancient metropolis was unearthed in the course of the implementation of an urban transformation project initiated by Turkey’s Housing Development Administration’s (TOKİ) in Nevşehir province of Central Anatolia.

While carrying out earthmoving works in the area, which was meant to be used for the construction of new buildings, the developers stumbled upon a massive underground network of cave tunnels, escape galleries and chambers spanning over 3.5 miles (7 kilometers).

In fact, it is not the first time when a subterranean settlement is found by accident in Turkey.

The region of Cappadocia, where the province of Nevşehir is located, is known for its historical and archaeological legacy as it once was a province of the Roman Empire.

When the invaders came, Cappadocians knew where to hide: underground, in one of the 250 subterranean safe havens they had carved from pliable volcanic ash rock called tuff.

Now a housing construction project may have unearthed the biggest hiding place ever found in Cappadocia, a region of central Turkey famous for the otherworldly chimney houses, cave churches, and underground cities its residents carved for millennia.

Discovered beneath a Byzantine-era hilltop castle in Nevşehir, the provincial capital, the site dates back at least to early Byzantine times. It is still largely unexplored, but initial studies suggest its size and features may rival those of Derinkuyu, the largest excavated underground city in Cappadocia, which could house 20,000 people.

The upper levels of the complex were first spotted in 2013, but its full size became apparent only at the end of 2014. Despite the fact that 90 million Turkish liras (around $35 million) have been spent on the project so far, the construction was postponed and the area was registered with Turkey’s Cultural and National Heritage Preservation Board. Till now, 44 historical objects from the site have been taken under preservation.

“It is not a known underground city. Tunnel passages of seven kilometers are being discussed. We stopped the construction we were planning to do on these areas when an underground city was discovered,” said TOKİ Head Mehmet Ergün Turan.

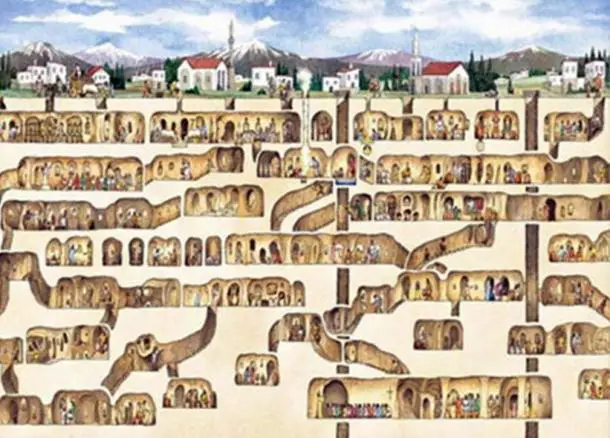

In 2014, those tunnels led scientists to discover a multilevel settlement of living spaces, kitchens, wineries, chapels, staircases, and bezirhane—linseed presses for producing lamp oil to light the underground city. Artifacts including grindstones, stone crosses, and ceramics indicate the city was in use from the Byzantine era through the Ottoman conquest.

Like Derinkuyu, the site appears to have been a large, self-sustaining complex with air shafts and water channels. When danger loomed, Cappadocians retreated underground, blocked the access tunnels with round stone doors, and sealed themselves in with livestock and supplies until the threat passed.

Cappadocia’s early adoption of Christianity—the apostle Paul arrived in the first century, and by the fourth its bishops were power players in the newly Christian Byzantine Empire—made it a safe haven during centuries of war for control of Anatolia. Muslim invaders arrived in the late eighth century, and centuries later came the Seljuk Turks. Eventually, Ottoman emperors ruled the entirety of Anatolia.

Turkey’s Cappadocia region is famous for its subterranean safe houses carved from tuff—a light, porous rock composed of volcanic ash.

While there is still very little known about the new subterranean metropolis, archeologists have already made some hypotheses about its possible function. Thus, Özcan Çakır of the Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University thinks that the city may have served for storing and transporting agricultural products.

“We believe that people who were engaged in agriculture were using the tunnels to carry agricultural products to the city. We also estimate that one of the tunnels passes under Nevşehir and reaches a faraway water source,” he said.

How Big Is It?

Geophysicists from Nevşehir University conducted a systematic survey of a 1.5-mile (4-kilometer) area using geophysical resistivity and seismic tomography. From the 33 independent measurements they took, they estimate the site is nearly five million square feet (460,000 square meters).

These studies suggest the underground corridors may plunge as deep as 371 feet (113 meters). If that turns out to be accurate, the city could be larger than Derinkuyu by a third.

“This new discovery will be added as a new pearl, a new diamond, a new gold” to Cappadocia’s riches, raves Ünver, the mayor, who wants to build “the world’s largest antique park,” with boutique hotels and art galleries aboveground, and walking trails and a museum below. (The planned housing complex has been moved to the suburbs.) “We even plan to reopen the underground churches,” he says. “All of this makes us very excited.”

Gülyaz’s team of archaeologists will continue to clear rubble from tunnels and explore deeper underground—a risky undertaking since the soft tuff is prone to collapsing. “When the underground city beneath Nevşehir Castle is completely revealed,” he says, “it is almost certain to change the destination of Cappadocia dramatically.”

We still have much to discover about this ancient underground city, and further excavation and archaeological research in the area will shed more light on this unique find.